This commentary comes from the Nepal Times. Per South Asia Revolution’s usual policy, posting here does not imply endorsement of the views presented. We will have on going series of articles and features related to the future of the Nepalese revolution. As this commentary suggests, events in Nepal are sharpening to a concentrated contradiction between the current dead-locked system, and a revolutionary transformation. Which characteristic will determine the Nepalese revolution in this period is yet to be seen.

“The message is clear: a significant faction of the Maoist party appears to remain committed to armed revolution as the only route to pursuing their political aims… Nepal’s politics has become so corrosive and so driven by patronage that any party coming close to power will be both compromised and consumed by it, abandoning both principle and ideology for the next pay-off. The Maoist leadership has now itself been swallowed up by this and increasingly alienated from its traditional base. The scary truth is that the radicals within the Maoists have been proved right by the gridlock of the last five years: there appears no capacity in the Nepali political system for social transformation, not even, it seems, for effective governance.”

The next People’s War?

The next People’s War?

A significant faction of the Maoist party remains committed to armed revolution

SIMON ROBINS in BARDIYA

The split within the Maoists is seen by many as a final test of their commitment to peace, and a test of the resolve and authority of Prime Minister Baburam Bhattarai.

However, this remains a metropolitan discussion, centred around the politics of the CA and trading of policies for money and position that has long defined Nepali politics. One faction of the Maoist party has already taken the discussion out of the Kathmandu back-rooms to articulate its position on a broader stage. For the last month, a Maoist cultural program, dominated by the hardline Kiran faction, has gone around the country laying out its critique of the peace process and more pointedly of both the position and integrity of the party leadership.

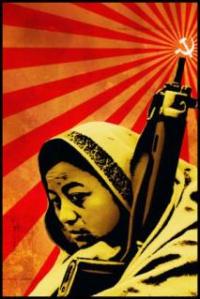

This program is a step above those organised during the ‘People’s War’, with a red tent, a sound system and headset microphones giving the performance the air of a tv show. The backdrop of the performance reveals its priorities: an armed PLA fighter in silhouette in front of a colourful explosion. The content has also evolved from traditional songs and dances of Nepal’s ethnic groups to a well acted, and often hilarious, drama.

The show tells the story of a Maoist CA member allied to Prachanda’s faction who now lives comfortably in Kathmandu with a new young wife, and spends his evenings in bars taking money for favours from businessmen. He has short shrift with idealistic party members from his rural district, while his constituents live in poverty, nostalgic for the ‘People’s Government’. The penultimate scene refers directly to the issue over which the Kiran faction has chosen to fight the party leadership: control of the PLA’s weapons.

A bizarre dance piece shows a group of PLA fighters committing to both the revolution and to never giving up their weapons, representing an almost obscene worship of the gun as a source of political power. The whole impression, sometimes looking like a North Korean Bollywood drama, nevertheless both entertains and moves the audience. The show’s denouement comes when a young party worker rejects the CA member’s bribes to work for his faction and returns to his village with a wounded PLA veteran, the wife of a man disappeared in the conflict, and an armed and uniformed PLA fighter, vowing to “continue the revolution”. The message is clear: a significant faction of the Maoist party appears to remain committed to armed revolution as the only route to pursuing their political aims.

The show clearly targets not the general public, but the party faithful, and appears to represent preparation for either an effort to overturn the leadership or, more likely, to break finally with a party that in their view has been compromised politically and ethically, and failed in five years of peace to advance the Maoist agenda in its heartlands. It is a message that will presumably delight those who have always maintained that in signing the CPA the Maoists were simply engaged in a confidence trick, confirming that there is no partner for peace.

What the message really represents however is even more disturbing. It is a statement that Nepal’s politics has become so corrosive and so driven by patronage that any party coming close to power will be both compromised and consumed by it, abandoning both principle and ideology for the next pay-off. The Maoist leadership has now itself been swallowed up by this and increasingly alienated from its traditional base. The scary truth is that the radicals within the Maoists have been proved right by the gridlock of the last five years: there appears no capacity in the Nepali political system for social transformation, not even, it seems, for effective governance.

The narratives that drive the political logic of the cultural programme are that many rural Nepalis remain in the state of poverty and social exclusion that provided such fertile soil for the ‘People’s War’, and that the sacrifices made by its victims appear to have been for nothing. The poorest communities who provided the fighters for both sides of the conflict have seen no significant change in their lives since the end of the war.

If the frightening message currently being heard from radical Maoists does lead to a second ‘People’s War’, the blame will lie not only with those who pick up guns, but with an establishment that has tolerated and fed a political culture that exists largely to sustain those at its heart. Baburam Bhattarai’s challenge is to quickly prove to

both the radicals in his own party and to the party’s traditional constituency that this need no longer be the case.

both the radicals in his own party and to the party’s traditional constituency that this need no longer be the case.

Simon Robins is a researcher and activist working with victims of conflict in Nepal and elsewhere

www.simonrobins.com

www.simonrobins.com